Mint 18 review: “Just works” Linux doesn’t get any better than this

This article was published in Ars Technica, you can view the original there, complete with graphics, comments and other fun stuff.

The newly released Mint 18 is a major upgrade. Not only has the Linux Mint project improved Mint’s dueling desktops (Cinnamon and MATE), but the group’s latest work impacts all underlying systems. With Mint 18, Linux Mint has finally moved its base software system from Ubuntu 14.04 to the new Ubuntu 16.04.

Upgrading to the latest long-term support (LTS) release of Ubuntu means, as with the Mint 17.x series, the Mint 18.x release cycle is now locked to its base for two years. Rather than tracking alongside Ubuntu, Mint 18 and all subsequent releases will stick with Ubuntu 16.04. Mint won’t necessarily get as out of date as Ubuntu LTS releases tend to by the end of their two-year cycle, but this setup does mean nothing major is going to change for quite a while.

If the Mint 17.x release series is anything to judge by, that’s a good thing. Stability allows Mint to focus on its own projects rather than spending development time creating patches for every Ubuntu update. That should be especially good news for the 18.x series since Ubuntu plans to make some major changes in the next two years: moving to a new display server (Mir) and updating its own Unity desktop to Unity 8 are chief among the priorities. Many of those initiatives will impact components that affect downstream users like Mint.

So if you’re looking for an Ubuntu-like system but don’t want to be Canonical’s lab rat for the transition to Mir and Unity 8, Mint is for you. Mint 18.x should make for a familiar but stable Linux environment.

In some ways, that means Mint has become what Ubuntu once was—a stable, new-user-friendly gateway to Linux. Mint installation is now simpler than upgrading to Windows 10 (though there is one additional headache with 18.0). And once installed, both the Cinnamon and MATE desktops will be familiar to anyone switching from Windows.

While Ubuntu’s Unity and GNOME’s 3.x series opt for sometimes radical changes, Cinnamon and MATE have taken a slower, more progressive path. Mint has elected to evolve overall rather than “revolutionize,” making it a far more comfortable choice for newcomers who aren’t likely to enjoy having the rug pulled out from under them every time they upgrade.

Mint’s slower, more evolutionary path seems to be serving it well, enabling it to play tortoise to Ubuntu’s revolutionary hare. These days Mint is one of the more popular desktop Linux distributions. While it doesn’t match Ubuntu’s total usage by a longshot, it draws the most interest of any desktop among the hard-core Linux users who read Distrowatch.

What’s new in Mint 18

Mint 18.x is well poised to continue to drive Mint’s popularity. It’s a solid release with some big changes, most of which won’t cause the average user any problems. Both Cinnamon and MATE look and behave more or less as they always have with a number of incremental improvements.

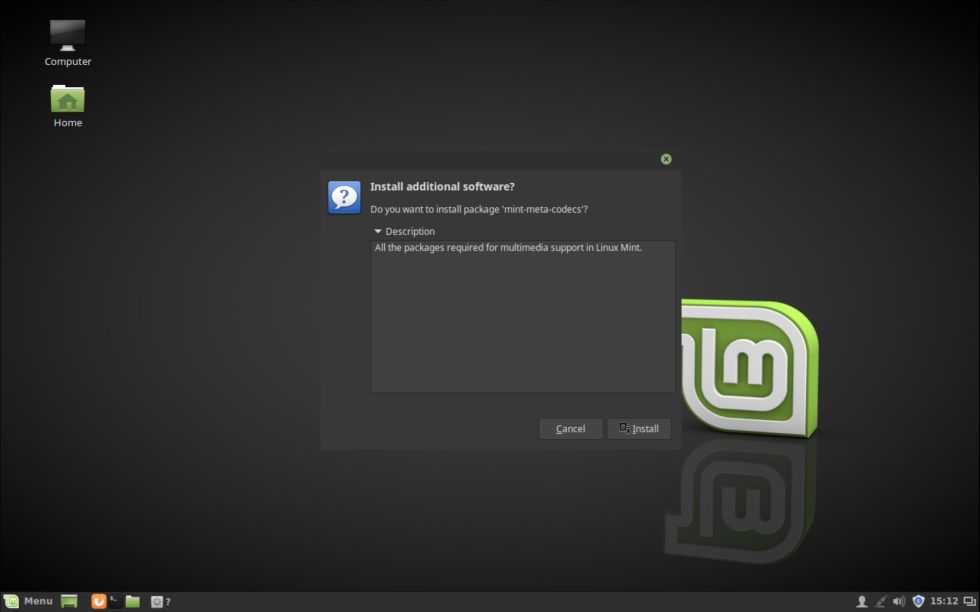

Mint 18 has a lot of updates under the hood, most of which the average desktop user can safely ignore. However, there is one change that will mean an extra installation step for many users. Mint 18 is the first Mint release to ship without patent-encumbered codecs and plugins. The change is a result of legal and copyright issues in some countries, particularly the United States.

To help out with the install there’s a new GUI app dedicated to installing multimedia codecs. It’s prominently listed in the installer, and if you don’t opt for it then, there’s an item in the start menu on both Cinnamon and MATE. This makes the process fairly obvious for new users, though the install is nowhere near as simple as having it just work from the start.

There is a new command line tool that will allow you to package up the codecs from the install disk (without having to have an Internet connection). It’s nice to see Mint is aware that not everyone who uses it necessarily has constant high-speed Internet connections. Too many Linux distros seem blissfully unaware that many of their users don’t have always-on, high-speed access (or worse, they just don’t care). It’s an especially nice touch since not shipping with codecs in the first place is really to appease the legal restrictions of US users while potentially dumping the bandwidth problem on those who could have had the codecs bundled legally.

Interestingly, if you happen to use the Chrome Web browser (not installed by default) and VLC for videos (also not installed by default), you might not even need most of the codecs, since both apps bundle the necessary codecs and plugins themselves. That really just leaves the MP3 codecs to install.

Straight out of the box Linux Mint 18’s flagship Cinnamon desktop looks just like its predecessor. The theme is still the “Mint X” theme that has been the standard for Cinnamon for years now. There is, however, change on the way. You can preview what will likely be the new default Mint theme at some point by heading to Settings >> Appearance and switching to the new theme, Mint Y.

As you would expect from Mint, it’s not radically different. It’s a bit flatter, buttons are less 3D, gradients have been toned down, and window bars blend into toolbars like they did in older versions of GNOME 3 (back when toolbars and windows bars were still separate things).

When the new look was first previewed back in January, there was a bit of an outcry from Mint users. Mint’s lead developer, Clément Lefebvre, addressed the pushback in a blog post that could well serve as a kind of Mint mission statement:

We’ve all witnessed the rise of the iPad and the iPhone. This was attributed to iOS somehow and it started a new trend with various projects trying to replicate Apple’s success, inventing new formulas and radically changing their own goals, focus or identity in the process. We’ve seen a new artistic trend called “flat”, with bright colors, no gradients and minimalistic widgets, taking these projects by storm. You don’t see us at the forefront of all that. We do keep a close eye on it, without any intention to jump into it, but rather to learn from it and to see if it can help us improve what we’re already doing.

People who enjoyed Linux Mint years ago still enjoy it nowadays. If you enjoy it now, chances are you’ll enjoy it still for a long time. You’re here because you enjoy it right now, we know that, we enjoy it too, and we’ve no intention of being anything else. So, in the context of that “new look and feel”, we’re not trying to reinvent ourselves. We’re talking about icons and GTK themes here. We’re also committed to supporting Mint-X, so with a click of a mouse you’ll be able to make Mint 18 look just like the way Mint 17 did.

Mint Y is, in other words, a nice evolution of Mint X with a nod to the current trend of “flat” user interface design. Yes, It looks similar to what GNOME, KDE, OS X 10.11, and Windows 10 are doing. Mint X looks similar to what GNOME, KDE, OS X, and Windows were doing six years ago—a decidedly “metallic” look to it that a certain fruit-themed OS also used around that time. Mint Y simply evolves to fit with the modern OS world. That’s part of what “evolutionary” means: changing to better fit the current environment.

Somewhere between then and now, Lefebvre and team must have changed their minds about making Mint Y the default, however. As of Mint 18 if you want to evolve the look and feel of Mint, you’ll have to do it yourself. If you’d like a slightly different feel, there’s also a very nice dark theme, Mint Y dark, and a hybrid of the two that uses dark toolbars and buttons with light panels.

The move to a flatter theme may be motivated by a good bit more than keeping pace with contemporaries in the style department; it may be related to another change in Mint 18—something called X Apps.

Mint 18 updates its base system to Ubuntu 16.04, which means that under the hood Mint 18 has moved from GNOME/GTK 3.10 to 3.18. Since GNOME does not adhere to Mint’s evolutionary philosophy but likes to make radical tweaks from point release to point release, there are some huge changes involved in moving from 3.10 to 3.18.

Sometimes this is a good thing. Mint 18 benefits from much improved HiDPI support, which is now just as good as GNOME’s. Accordingly, Mint has been able to add popular apps like Spotify, Dropbox, and Steam to its repos, making them much easier to install.

The move to GNOME 3.18 is not, however, without its downsides for Mint. As Lefebvre writes in the same blog post, “GNOME applications now integrate better with GNOME Shell and look more native in that environment. The bad news is that they now look completely out of place everywhere else.” For Mint, the issue is further complicated by being downstream from Ubuntu, which heavily patches GTK, GNOME applications, and the GNOME environment itself.

In the past Mint has dealt with this problem the same way Ubuntu has: downgrading apps and patching where necessary, occasionally patching on top of Ubuntu’s patches. The changes in GNOME 3.16 and onward make this extremely time consuming and impractical, however.

Instead Mint has decided to create X Apps. No, the distro isn’t building out clones of GNOME apps. Lefebvre rejects this idea. “It was decided early that Cinnamon would not get its own applications,” he writes. “It represented too much work and there were too few differences in application needs between Cinnamon, MATE and Xfce.”

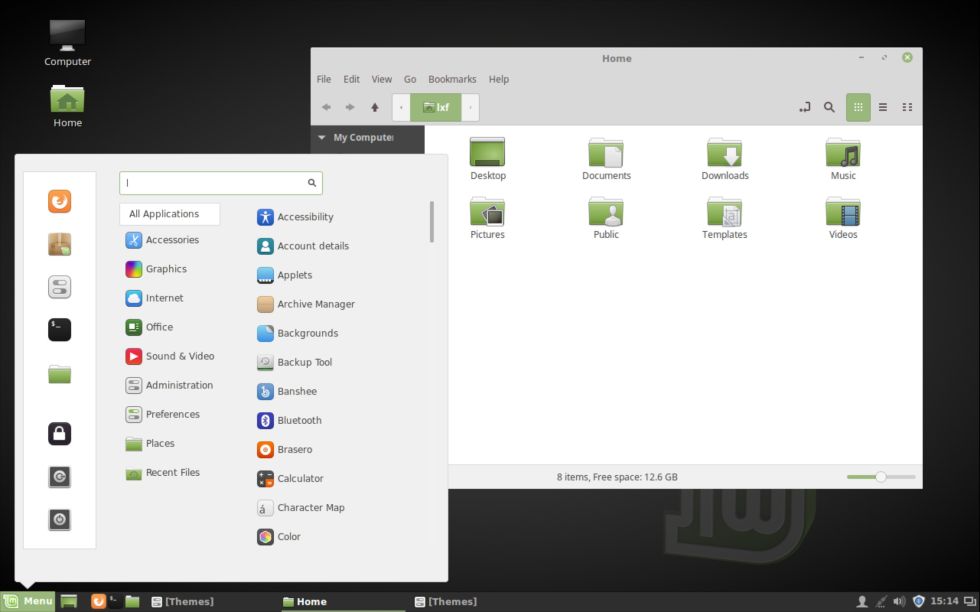

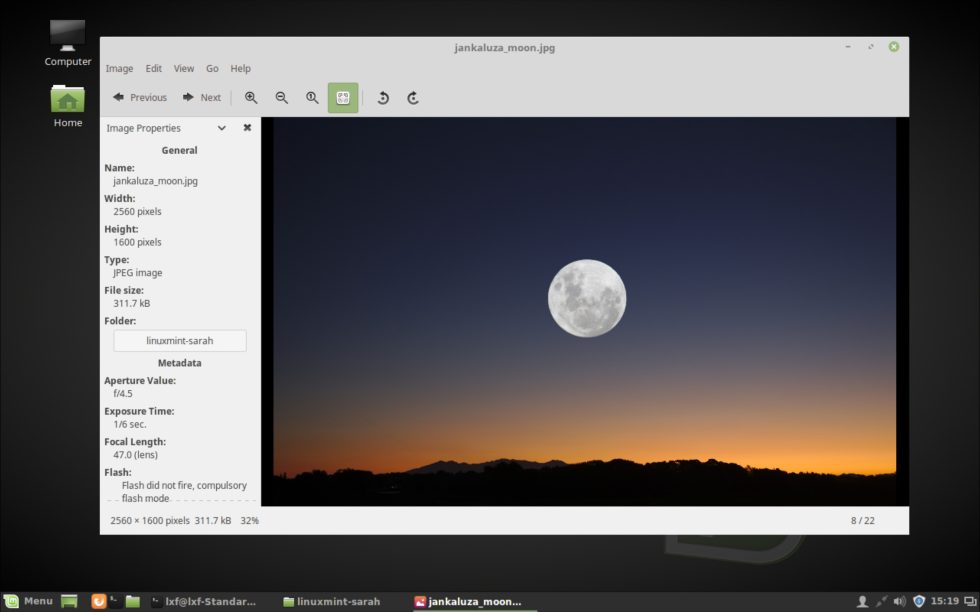

Essentially what X Apps does is take GTK apps and re-theme them in a way so they’ll look at home on all of Mint’s desktop releases, Cinnamon, MATE and Xfce. For Mint 18, there are five X apps: Xedit (a text editor), Xviewer (an image viewer), Xreader (a PDF/document viewer), Pix (a simple photo organizer), and Xplayer (a video player).

In the end, X Apps become a seamless part of the Mint 18 experience. Users don’t really need to know the Xplayer is a heavily themed and patched version of Totem or that Xviewer is Eye of GNOME. What’s even nicer is that the X Apps get all the underlying features that make modern GNOME apps nice, namely HiDPI support and support for customization via gsettings.

Another change to be aware of in Mint 18 is that Mint’s homegrown “apt” command now supports Debian’s command of the same name. Mint’s apt was originally a shortcut for a handful of package-related commands, including apt-get, aptitude, and apt-cache. Since Mint’s apt debuted, Debian has created a similar shortcut. Since tutorials typically refer to the Debian version, Mint has updated its tool to mirror Debian’s version. Mint’s apt, however, still supports all its own commands, many of which Debian’s does not.

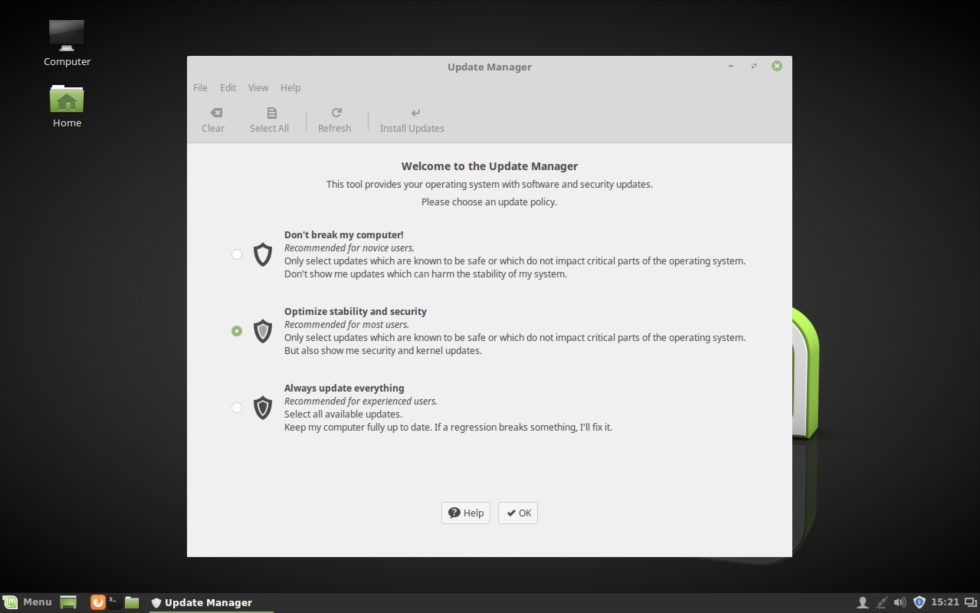

As has been the case for just about every Mint release in recent memory, Mint 18 ships with a number of improvements to the Update Manager. The biggest change is a new overall setting for updates. Users can choose from three options. There’s the very safe choice, which is to update the system with stable versions of software. Then there’s the default, which is to do the same as the safe option but also show additional updates which could cause instability. This allows you to choose what you want to update beyond the stable versions available.

The last option is the make-it-like-Arch-but-without-the-testing option to always update everything. The latter is not recommended unless you know how to boot to a shell and roll back updates when you break something. Again, even though most users don’t need anything beyond the default, it’s nice to see Mint adding options (and if you find yourself using the third option, you might want to consider trying Arch).

The Update Manager also greatly simplifies its kernel update options and now just links to changelogs instead of trying to pull them in.

The kernel update feature in Mint is probably the simplest GUI means of updating a kernel I’m aware of in any distro. That’s something of a mixed blessing of course since this is also probably the tool by which it is easiest to really screw up your system.

That might be part of why, when you first launch the kernel update panel in Mint 18, you’ll also get a very nice explanation of what a kernel is and how badly you can screw up your system if you try to use the wrong kernel. Linux Mint 18 ships with Linux Kernel 4.4.0.21, though, when I tested the distro, several newer kernels were available up to and including 4.4.0.28.

What’s new in Cinnamon

Mint 18 ships with Cinnamon 3.0. In keeping with the evolutionary nature of Mint-related projects, Cinnamon 3.0 is not a radical departure from the past. This is a careful refinement of existing features and some new customization options.

Cinnamon is not a tiling window manager by any means, but it does have an interesting window-snapping form of tiling that has been improved in this release. It’s a long way from Xmonad or Awesome, but if you’re a casual tiler it will allow you to tile your windows when you want to.

A more useful change is the ability to eliminate potentially unused cruft from the start menu. Right-clicking the Mint button will bring up the customization screen with new options to hide favorites, bookmarks, system settings, and other infrequently used items. The result is a cleaner start menu if you want such a thing. It’s not a feature that everyone will use. In fact, I didn’t use it, but I like that it’s there. It’s encouraging that Mint is still developing features useful to only a small segment of users and hasn’t caved to the tyranny of the majority like certain other desktops.

Similarly, Cinnamon 3.0 offers some new accessibility settings, which have been re-written as native Cinnamon-settings modules. It’s now easy to toggle larger text, high contrast themes, and turn on (or install) GNOME’s Orca screen reader.

Panel launchers get some new features in this release, namely support for application actions. This means, for example, that you can launch a new Firefox window from the launcher icon. Which actions are supported varies by application, but at a minimum it consists of opening and closing new windows.

What’s new in MATE

The MATE-specific changes for this release are relatively minor. The MATE version contains all the Mint updates like the new theme options, the revamped Update Manager, and new X apps. Beyond that, MATE’s changes are small.

There’s new GTK support under the hood, which means better HiDPI support, though MATE is still a long way from the best choice for HiDPI laptops. The MATE touchpad preferences get some new options to configure edge and two-finger scrolling independent of each other (this is available in Cinnamon 3.0 as well).

Performance

I tested Mint 18 on the Dell XPS 13 that I reviewed last month on Ars and found it to be a snappy desktop, considerably less resource hungry than the default Unity that shipped with the Dell. Cinnamon is the flashier of Mint’s desktop options and uses a bit more memory (about 450MB with nothing running but the default startup apps), but it’s still quite a bit less than Ubuntu 16.04 (about 650 MB with nothing running but the default startup app). In fact, of what I would call the four heavyweight Linux desktops—GNOME 3, Unity, KDE, and Cinnamon—Cinnamon is the least resource intensive.

If you’re looking for something a bit lighter, Linux Mint MATE is the way to go. It lacks the level of HiDPI support that Cinnamon offers (which makes it difficult to use on the Dell XPS 13’s HiDPI screen), but for older hardware it’s the obvious choice. There’s also an Xfce version of Mint, but as of the time of writing it has not yet been updated to Mint 18.

Both Mint desktops feel snappy on modern hardware. Even Cinnamon’s on-by-default animations don’t introduce the kind of millisecond interface lag that I was, frankly, expecting. Of course testing on less modern hardware like an old EeePC reveals a starker contrast. Of the two, MATE is the better choice in situations where RAM is limited.

Conclusion

Linux Mint 18 is a solid update and continues the slow but steady evolution of one of the most popular Linux desktops out there. If you’re an existing Mint user, it’s definitely worth upgrading, though do bear in mind that this upgrade may be a bit more difficult compared to the very simple upgrade process for 17.x updates. As of this writing, Linux Mint has not published its usual upgrade guide, and I installed a clean copy, so I can’t comment on the upgrade process.

Mint 18 remains my recommendation both for anyone who’s new to Linux as well as seasoned Linux users who want a desktop that just works and gets out of the way. Thanks to its incremental development approach, its dedication to evolving features slowly, and its development of power user features and configuration options, Mint manages to serve both newcomers and Linux power users well.